Boozy Pheasants, Fly-Fishing and Other Life Lessons.

So it’s Hogmanay, and as I start, 2020 sits on the horizon. As the new decade morphs from teenager to adult, and I ponder the teen years, tomorrow may be a blank page but much has been written in the last ten.

In the blink of an eye I’ve seen my son’s go from boy’s to men. It marks ten year’s in business. The loss of our beloved best friend Cameron, taken too soon by suicide, his friendship now a treasured memory. Personally, it has been a decade of lost and found woven in contrasts of light and dark. Mother, Maiden and now Crone; as I edge ever closer to fifty. The last ten years have been both a blessing and a lesson. I discovered not all storms come to disrupt, some come to clear your path.

Change is evolution and if it doesn’t challenge you, it won’t change you. However, in recent times, the changes have been troublesome and disconcerting. Rather than feel progressive, culturally and socially, one can’t help but think we are regressing. This last half has seen a resurgence in nationalism and division. People like Johnson, Farage and Sturgeon. Trump, a puppet who wilfully stokes the flames of hatred, contaminating, his putridity infects like a pandemic. Just this week, his warmongering escalating conflict with Iran. He is the cycle of Ouroboros, the snake eating its tail – terror feeding chaos.

The backlash has resulted in recoil. Borders, walls and wars. Cages and detention camps. The Indy Ref, Brexit and a General Election, has left us frightened, confused and selfish. It’s now a society with a palpable lack of empathy. But as much as the cruelties of this world really upset me, it’s humankind’s avarice and lack of compassion that I struggle with the most. In particular, society’s all take and no fucks given, seemingly blatant disregard for Planet Earth.

As I write the Southern half of Australia burns. The catastrophic fires raging largely the result of rising temperatures. Each new year brings the inevitable reflection, and as Christmas Present rages red, it reconnects me with my ghost of Christmas Past. Because when I think of Mother Nature, instinctively, my mind drifts back to my childhood and of time spent with my Granda.

Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world’s great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs.

I am haunted by waters.

-Norman Maclean

I’ve no idea why I was up so early that morning, but I’m pretty sure it was a Sunday when the Police came to our door.

Feet up in front of the coal fire, I am just about to take a bite out of my buttery covered in homemade raspberry jam, when I hear a knock at the front door. My granny comes through from the kitchen, drying her hands on her apron asking “fa’s at knocking at this time in the morning?” Low voices are talking, but I can’t make out what’s being said. And then I hear it, a thud then a wail so acute that it makes my stomach clench. I bolt up from my seat but then stand there frozen, jam dripping onto my bare feet; after what feels like forever, I finally make a move. Through the etched glass door, I can see silhouettes. One is lying on the floor, and the only sound now is sobbing.

I was eleven when just before Christmas, my Granda died in a car crash. He’d left before first light that morning, the salmon were running, and he could never resist the take. On route, the car skidded on black ice and overturned, he died at the scene.

Long ago, in Kentucky, I, a boy, stood

By a dirt road, in first dark, and heard

The great geese hoot northward.

I could not see them, there being no moon

And the stars sparse. I heard them.

I did not know what was happening in my heart.

It was the season before the elderberry blooms,

Therefore they were going north.

The sound was passing northward.

Tell me a story.

In this century, and moment, of mania,

Tell me a story.

Make it a story of great distances, and starlight.

The name of the story will be Time,

But you must not pronounce its name.

Tell me a story of deep delight.

-Robert Penn Warren

Along with the robin and that first foil of bonfires, when the amber turns to usher Winter in; resounding, the recognisable klaxon that Winter is coming. I stand beneath the geese, close my eyes and listen; and at that moment find the past.

In Greek, nostalgia means “the pain from an old wound.” It is a twinge, a knawing in your heart more potent than memory alone; that place where we ache to go again. Nostalgia can put people on pedestals, rose tint the negatives. Of course, I know my Granda was far from perfect; but to me, he was the story behind my story.

I came very close to being born in a Mother and Baby Home. Which sounds like a problem solved, but history tells it differently. It was 1970 and in my neck of the woods, they’d yet to embrace the revolution of the Sixties. A town of small minds and sharper tongues that salivated at the merest hint of gossip. And illegitimacy was big news; the curtain twitchers loved a scandal. So, if it hadn’t been for my Granda, who flat out refused the suggestion, I dread to think. He said the day I was born was the happiest of his life.

My upbringing was dysfunctional, circumstance and familial histrionics made it confusing and chaotic. But Mother Nature knows no prejudice, and my granda knew this. When I look back now, without a doubt, he utilised the natural world to buffer me from the cruelties of the adult one. Unknowingly, Nature became my haven, I ran free, and it was my Granda that nurtured the wild in me.

In The End We all Become Stories

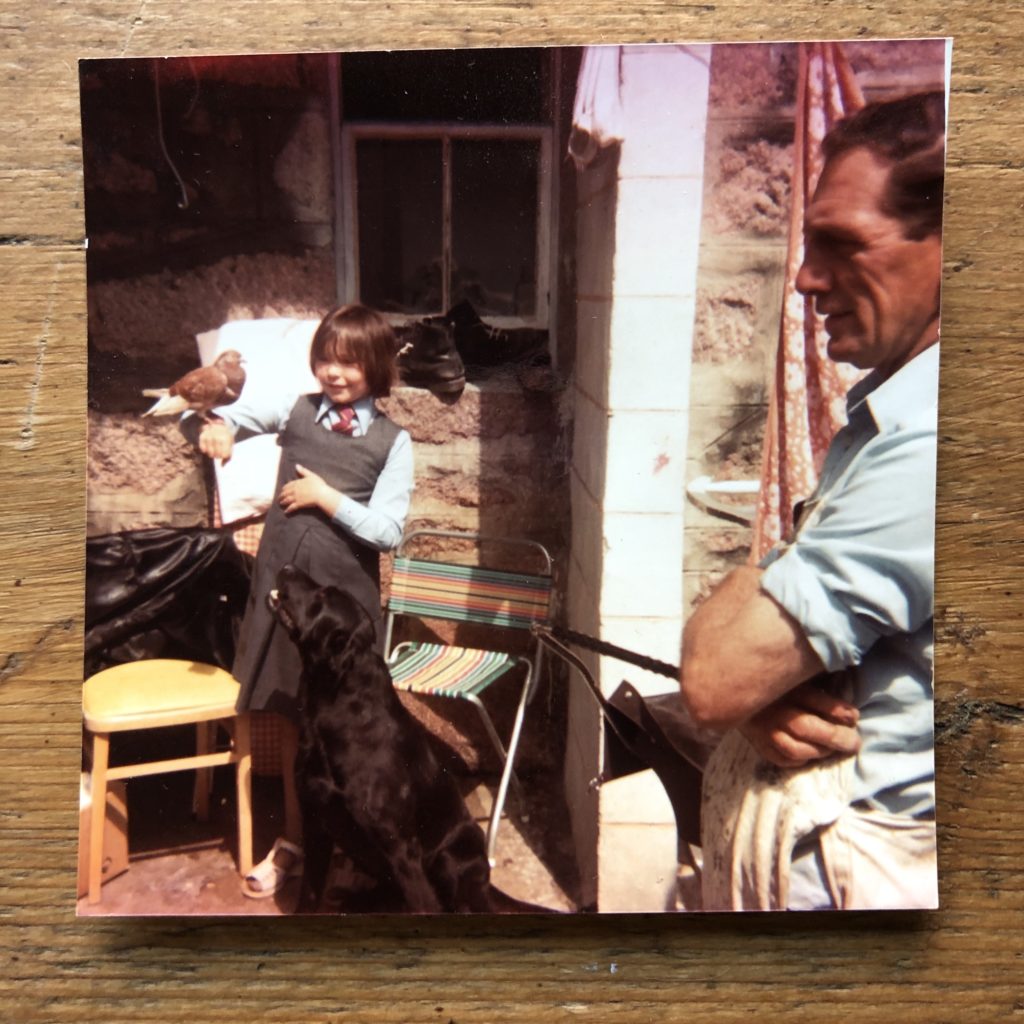

My Granda Georgie was a handsome kindly man, one who smiled with his eyes. He smelt of Old Spice, rolling tobacco and contentedness. Painter’s dungaree’s or waders, dark curly hair swept back with Brylcreem, his skin tanned conker from a life spent outdoors. His environmentalism was simple: Respect Mother Nature, be kind to her and always give something back. It was he who introduced me to the science of evolution with stories of Charles Darwin, and his voyage of discovery to the Galapagos Islands. And despite incurring my Granny’s wrath, with a wink and affectionate prod, that my coccyx “was where my tail used to be.”

Granda was ill-tricket; he was always up to something, and I was guaranteed to find it funny. On holiday, sitting on a bench outside the ice cream shop, he say’s “watch this.” He had a five-pound note attached to

I sit here smiling, warmed by small things easily forgotten. Such as him super glueing a 50 pence to the kitchen worktop or in the sugar bowl, the teaspoon with a hole and the paper bag trick, Eric Morecambe style. Or sticking a marrowfat pea up his nose and then pretending he had found the world’s biggest bogey.

Collect Beautiful Moments

Holidays were always an education. First time I ever rode was on holiday, age four where I was plonked on a small Highland pony. That day was to ignite a lifelong love of horses and horse riding. We had a Volkswagen camper van and every summer we’d head off, usually the West Coast or the Highlands. Conveniently, somewhere that also had good fly-fishing and mountains. Hill walking, like it or not, was obligatory.

Although when I think of our holidays, it’s Invergarry I remember most. A small village in the Highlands, nestled in the Great Glen between Fort William and Fort Augustus. The glen is taken up by a series of loch’s – the largest Loch Ness, with a series of river’s connecting them. An angler’s dream, and perfect for a kid with a vivid imagination, especially when it came to tales of the Loch Ness Monster. Even now, if we are up that way hill walking and drive past the loch, despite logic, look, still hoping to catch a glimpse.

While there, we stayed with a friend of my Granda’s, Jock who was a ghillie for Invergarry’s rivers. He and his wife Mary, lived in a traditional white stone cottage by the River Oich. It was as picturesque as it sounds. When I think of there, I remember my Granda and I making daisy chains and beaded necklaces from red Rowan berries. Of him telling me that the Rowan was sacred and taboo to cut one down. And that if you ever needed to find water, to use two of their branches as divining rods.

I remember Jock and Mary’s wee white cairn terrier, and the scary cows in the field next to the cottage. There was a wee shop across the river and up the hill. But to get there you had to go into the field and past the herd. And cows being curious beasties would follow you, scary stuff when you are little. Of overhearing conversations where they discussed poachers, boozy pheasants and catching fish with cat’s tails. My curiosity got the better of me and later that night, I just had to ask. It was worth confessing I’d been ‘lugging in’ so I could find out about drunk pheasants and cats.

He told me poaching is illegal and poacher’s would often use furtive measures to avoid the police. So, pheasants are partial to raisins, especially if they are soaked in booze. The alcohol makes them bit drunk, sleepy and easy to catch – hence boozy pheasants. As for fishing with cats?

Cat Got Your Tongue?

That holiday my Granda had caught a few sizeable fish and Jock, disgruntled (there’s always a healthy competition and friendly rivalry between anglers) wanted to know how he’d managed it. Now, anglers will happily share a catch but never their secrets, but perhaps after a few drams, he was feeling generous. Or more likely, because Jock didn’t own a cat, my Granda knew he couldn’t capitalise on the secret. One such cabal was tying your own flies, something at which my Granda was particularly skilled. If you created one that was a success, you guarded it with your life. If my Granda had a particularly good catch, and was asked “fit’s biting?” He’d always smile and reply “the end of my line.”

In making a fly, it’s the study of entomology and the more realistic the better. In this instance, as he informed Jock, cat’s hair was the trick, specifically, a teeny bit of fur from the tip of the tail. Which also explained why our ginger tom sometimes went around with an odd looking tail.

I often wondered if our cat played a part in my Granda landing, reputedly, one of the largest salmon ever recorded from the River Ugie. The pink fish was a whopping 36.5 pounds, so huge it had to be stored in the bathtub with ice until the local press photographer came. In the photographs, my Granda is seen holding up the leviathan by the gills, but that his fingers are awkwardly placed over the fish’s nose. Turns out, something had gotten into the bathroom and eaten the tip off the salmon’s nose. I reckon it was the cat, payback for having a flat top.

Creature Comforts

There were always creatures in the house, some pets, some there to do a job, like our gun dogs and ferrets. I was taught to care for the animals; as they too were family, no different from us and their welfare as important as our own. Especially the ferrets, you don’t want a disgruntled ferret, trust me.

Because he was outdoorsy, he often brought home injured or abandoned animals. When he came through the door with a cardboard box, you were guaranteed a surprise. I remember like yesterday the time he took home an injured barn owl he’d found at the side of the road. Or the first time I saw a hedgehog, but the poor thing was infested with fleas. But my Granda ever the optimist informed me this was a bonus, because we could now use them to start our own flea circus. He said we could keep them in a matchbox and teach them tricks. The things you believe when you are a kid.

He was an old school hunter-gatherer and crack shot. So, in our house, you ate what you caught, and it was usually game or fresh fish for supper. It wasn’t uncommon to wake of a morning to the smell of wild mushrooms, freshly picked, served up with homemade pancakes. He trained as a baker during his National Service so could bake all sorts; his salted loaves hot out of the oven with butter was the stuff of legend. And he could crack two eggs with one hand.

On the subject of eggs, I remember him teaching our black Labrador Billy how to pick one up without breaking the shell. The surest way to learn a gun dog how to carry a bird without damaging it. Want to teach a dog to be patient? A small biscuit on the end of a dog’s nose works wonders. That’s if you can stand to watch strings of drool as they yo-yo.

I am longing to be with you, and by the sea, where we can talk together freely and build our castles in the air.

– Bram Stoker, Dracula

My town is a small coastal town, one steeped in myth and superstition. With a history that stretches back to the time of Jacobite Rebellion, Spanish Pirates, the first Arctic Whalers and Bram Stoker— wedged between cliffs and brackish waters, where the spate river Ugie flows to the brooding Atlantic. Here in my corner of the world, the North Sea is master to all, from rolling goldfields to green forests of Pine and Birch. I am bound to Nature, the Sea; the salt’s in my blood — the sound of waves, their ambient white noise. A sound one takes for granted, but miss the most the minute I am away from home.

I lived a stone’s throw from the shoreline and mere minutes from the harbour, and there my Granda kept a ‘ripper’ boat. A small yawl, built for inshore ripping; the technique of hand-lining with weights and hooks for cod. That was back in the days when cod was plentiful and could be found nearer the coast. He also set out crab and lobster pots, and picked sea urchins. Most of which he sold at the early morning market, the rest came home for the table. Although, delicacy or not, there is nothing in the world that could make me eat urchin innards. The fact the only edible part is their gonads, is enough said.

Me being a girl made no difference to my Granda, I was taught there was no reason why I couldn’t do all the things normally considered the preserve of boys. So I grew up unconstrained by bias; I learned how to shoot, fish and stick up for myself. Best of all it meant I got to go with him when he went out in his boat, Rosie. Which, coincidentally, was the name of my first pony; but then there is no such thing as coincidence. He’d always promised me one, but circumstance meant he never got the chance. So for my thirteenth birthday, my Mum and Granny clubbed together and on behalf of my Granda, bought me her. Cesar Milan writes “you don’t always get the dog you want, but you get the dog you need.” Still swamped by grief, my need, instead was a 14.2 golden Palomino named Rosie.

“Eence a ship sailed round the coast

And a’ the men in her was lost

Burrin’ a monkey up a post

So the Boddamers hanged the monkey-O”

Heading out through the North Breakwater towards Skerry Rock, which I translated as scary rock, after my Granda told me the tale of hanged monkey of Boddam.

Skerry Rock is a pointy outcrop that sits in the sea, approx a mile from the coast at Boddam, a small fishing village near Peterhead. The story goes that in 1772 villagers purportedly captured and hanged a monkey who was the sole survivor of a shipwreck. Now, apparently, the reason for killing the monkey was because they could only claim salvage rights of a wreck if there were no survivors. However, my Granda told me the real reason was that the villagers didn’t know it was a monkey. And because they were so superstitious and god fearing, they thought it was a hairy devil and hung it for fear of a curse. The tale underpinned a long standing local feud and between rivals, asking the question of “fa hingit the monkey?” was considered a slur. Rumour has it, even today, villagers still consider it so. No offence meant, neighbours.

The North Breakwater, incidentally in part, was built by my great grandfather Keith Milne; as he and his two other son’s Gavin and Tony were deep sea divers. My great grandfather ran a diving business, one that was contracted to lay the bedrock of the Breakwater. Using colossal blocks of granite, its foundations built from the sea bed up. To do so, they sank like stones, plummeting into the void, all that connected them to survival was trust and a manual umbilical. Dressed in hulking suits of copper and brass with boots so heavy it took two men to lift. One can’t imagine the courage required to do that job. Knowing once you were down, there was no way out or up without help. Suspended, held hostage in an alien environment.

The Cure For Anything Is Salt Water – Sweat, Tears Or The Sea.

I loved going out in the boat, early mornings were my favourite. The rhythmic chug of the engine contrasted by the cut of the motor. Rocking slightly as the sea cradled the boat, watching as the petrol made liquid rainbows in the water. A sunrise that reflected back in hues of gold. Or dark blue days when a salt tang on the wind portend the storm coming.

Albeit it took a few lessons, but I learned how to handle crab and lobster without losing a finger. To always put the juveniles and small catch back. How to gut and fillet a fish, how their scales stick and stuck glittering on my skin. To use the waste as bait or to feed the dog-headed seals that followed the boat. Bar the seagulls, there was never a soul to be seen, and it felt like the world belonged to us.

Fortunately, I was born before mobile technology and playtime meant using one’s imagination. So as soon as school was out, I was off, out ‘doon the rocks’. We played, cocooned by the remnants of the old port, its walls smoothed by the harshest of seas. Low tide left the harbour steps slippery, but it also trapped secrets. I can still remember the day I found a brightly-coloured goby. Normally it was sticklebacks or as we called them bandies. Their redbreasts flashing left and right, as we scooped our nets into the water. The goby was a rare find. We usually kept the haul in a tin bucket filled with seawater, and released them back before we went home. But this day, with my imagination running riot, I sprinted home, bucket in hand, to show my Granda. I didn’t know what it was, and I was desperate to find out.

I spent my summer’s barefooted and thigh-deep in rock pools; my skin brown and freckle kissed from the sea breeze. Oh, how I loved making ‘shoppies’ with flotsam and jetsam, collecting jewelled sea glass and opaque mermaid’s purses. Trading our finds, using limpets and winkles or buckies in our lingo, as currency.

No foreign holidays for us, I was eighteen before I went abroad. But it was no hardship. Miles of golden sand with crystal clear waters that coloured from turquoise to grey-blue depending on cloud cover. We would usually stick to low tide and hotspots where the sun had warmed the water. But sometimes, if we were feeling courageous and ignoring the bitter harsh of the North Sea, we would crash head first into the waves. It is exhilarating and to this day, I still wild swim, there is no freedom like it. Family, cousins and friends, we’d all pile down to the beach. Blankets, sandwiches and flasks of sugary tea. And ice-cream. Sprinting back across the Birnie Bridge, pennies in hand to get a cappie (doric for ice-cream cone) from the van. Nothing beats eating ice-cream while warming your feet in the sand.

“I fish to scratch the surface of those mysteries, for nearness to the beautiful, and to reassure myself the world remains. I fish to wash off some of my grief for the peace we so squander. I fish to dip into that great and awesome pool of power that propels these epic migrations. I fish to feel – and steal – a little of that energy.“

– Carl Safina

If I wasn’t doon the rocks or out in the boat, I was up the river. Because in our house, fly-fishing was a religion, the salmon revered, its life intrinsically linked to our own. Derived from the latin word, salire meaning ‘to leap.’ The fish of wisdom, ethereal; master in the realms of both fresh and saltwater. Teaching us everything is connected and all rivers run free. Instinct calls to them and using inherited magnetic maps, they traverse thousands of miles while heroically, swimming against the odds. They follow the scent of their ancestors, until finally, they reach that place they call home. The salmon’s life is an odyssey, of birth, migration, restitution, procreation and death; the cycle of life.

I was taught to step ‘into’ the river. In order to catch a fish, one must become. Standing hip deep in white rafts, I learned to read water; feeling its ebb and flow, the pull and swirl of the current. It was hypnotic to watch my Granda cast-off, I’d stand observing, alert and silent, watching magic at work.

He then gave me one of his old rods, a treasured Greenheart Scott s4 (if I remember right) and slowly, I came to grips with a four count rhythm; step-cast-wait, cast-wait, cast-wait, step-cast-wait. Ten o’clock, two o’clock. There is an alchemy to fly-casting, the rhythmic movement that becomes a dance of one’s arm and mind. The spring of the rod, spellbound by the cast, that gentle swoosh as the line catches the air. To fish is a fine simplicity, hours are like minutes as one waits patiently as the river billows over moss-covered rocks.

My Granda shared techniques he’d honed over decades, his rituals and secret places.

Fish are intelligent and evolved to be supreme masters of survival. There’s many an angler been outsmarted by a fish, and most have a story of the one that got away. Some even have a nemesis, I know my Granda did, a battle of wits to try and catch that one elusive fish. My Granda was a solitary angler, and I didn’t always get to go with him, so the days I did were a privilege. Silence is key, so there was no talking, which when your wee and have a thousand questions, is hard to quell. But as author Harry Middleman writes “the fly rod itself, is a tool for conversation that speaks not in words but motion and energy.” Fly-fishing taught me patience and that all good things come to those who wait.

With the merest hint, a tweak of the fly, the fish stirs a primitive instinct. The trick now is knowing when to lift the line. It takes! And the real test begins. You have to suppress the excitement and focus. Until it breaks the water, the fish remains unseen and one must rely on the senses to reel it in. Lest we sever the connection, one must respond with respect, it is more of a coax than a catch. The fish is magnificent, stalwart in iridescent steel blue grey, its spots like full stops. And although we mostly fished catch and release, to handle this noble creature was gift enough. It was like holding time itself.

After he died, I did go fly-fishing by myself, and although I was used to silence, the absence of his presence was just too much to take. But if you turn your face to the sun, the shadows fall behind you. Yes, I had my grief but with it I found my relationship with Nature deepened. And like spider silk, glistening; weaved between reeds, our spirits remain intertwined.

My admiration for the salmon and all things aquatic eventually led me to study marine biology, specialising in genetics and gene mutations in farmed fish. Working for a research facility at Aberdeen University. My career took me from fish farms to oil rigs, from the West Coast of Scotland to Canada. I qualified as a diver, learned to kayak and experienced a life less ordinary. Especially in Canada. I’ve written before that my time there, not only changed my life, it saved it. My Granda always wanted to take us to either Canada or Alaska, to witness one of Nature’s great events; grizzly’s fishing the salmon run. Sadly, he never got the chance. But when I did, I made damn sure, I experienced enough for the both of us.

Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than

sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity.

– Martin Luther King, Jr

The Earth’s 7.6 billion people represent a mere 0.01% of all living things. Yet since the dawn of civilisation, humanity has caused the loss of 84% of bio-diversity. Of all mammals, 96% are livestock and humans, only 4% are wild animals. The word humanity is a noun; of humans being collectively. But also means; the quality of being humane; benevolence. Given our paltry insignificance, our capacity for destruction is staggering. Like a plaque, we have successfully managed to decimated the world in ways worse than global warming alone. We arrogantly label ourselves the most intelligent species on Earth; yet in the same breath, destroy the very thing that sustains us.

It’s also no coincidence that as we systematically demolish the world, we see a decline in well-being and mental health. It is a population bursting at the seams fuelled by toxic, insatiable consumerism. Without question exploitation manufactures depression.

I rage when corporations and politicians tell us Climate Change is fake news or a conspiracy theory. Especially when those same people profit from deliberate disinformation and receive millions in political contributions from the fossil fuel industry. But I am not here to try and convince you, because the facts are out there and the signs are everywhere. To see it, one just has to open their eyes.

I talk of the last decade and here in Peterhead, the last time we had a proper winter was 2010. A few years back, just before Christmas, I remember sitting in my garden and the barometer read 14 degrees celsius. When hillwalking, every year we see less and less snow on the hills. I planted a Buddleia to help attract butterflies, but over the years, I’ve watched their visits become fewer and numbers dwindle. As phobic as I am, the lack of moths flitting around the nightlights is noticeable. That each year the ivy that adorns my outside walls, flowers later and later – thus out of sync with the honeybee’s and other nectar and pollen collectors. Or that it’s early January and my Black Cherry Plum Tree has already started budding.

Perhaps some people have no interest in or ever had a connection to Nature, therefore, sadly, cannot comprehend the enormity of what’s going on around them. I also empathise with those less fortunate, and appreciate that the plight of the Planet may be the furthest thing from their mind.

But the climate deniers baffle me. As does the ardour with which they deny it and ridicule those trying to make a difference. So what if it were fake news? Can someone please explain, how nurturing the one thing that sustains us, possibly be a bad thing? Would you really rather cut off your nose to spite your face?

And as I was watched Australia burn, of people and creatures dead, displaced and homeless. Tweets and posts offer prayers, presumably to the same God responsible for the fires in the first place. But you can’t have your cake and eat it too. Pray may be a doing word; a verb, but the reality is it does nothing. No matter how much it appeases your conscience.

He is the richest who is content with the least,

for content is the wealth of Nature.

– Socrates

My best advice is try and live a simpler life and get outdoors more. I guarantee you, the less you want, the happier you will be. No matter the contribution, you can be the change; because the little things mount up to a lot. Greta Thunberg proves you are never to small to make a difference.

Mostly due to human impact, the wild salmon population is in decline, with catches at their lowest levels since records began. The Orca’s of Puget Sound are dying, starving to death, the population almost extinct. Because they’re main food source, the King Salmon is now also an endangered species, and what little remains of the fish is toxic. It breaks my heart to read that analyses under current environmental conditions, predict the extinction of the Southern Resident Orca population by 2050. Given our kinship, and my connection to both creatures, I can’t think about this without crying.

Our lives changed dramatically after my Granda died, and I often wonder what would have been if he were still here. I counter the grief with the consolation that everything happens for a reason. While his death sent me down a path I wouldn’t choose for anyone, it eventually led me out and to my husband. When my youngest was born and they laid him on my chest, his eyes were open, and in that moment I knew we had met before. The deja vu comes in a fleeting glance, it’s in the curl of his hair or the silhouette of his stance. My Granda now more than memories pressed behind glass.

Nature is resilient with an incredible capacity for healing; one that can even help mend a broken heart. So if we were all to do our bit, she can recover. Of the many life lessons learned from my Granda, what stands resolute is that time in Nature is never wasted. Mother Nature and society have become strangers. I think it’s time we came home and made her reacquaintance.

Because Nature Never Did Betray The Heart That Loved Her.